Rings Around The World–a new exhibit and the first in our series of diverse stories on rings

More than any other category of jewelry, rings act as visual celebrations of the most memorable moments and emotional connections in a woman’s life, commemorating birth, betrothal, friendship and mourning. They have become the cherished talisman of self-purchasing women, the millennial generation and those who want to project their personal style through sentimental and symbolic antique rings or minimalistic or ornate modern styles. They can be worn stacked or singular and statement making, or in mixed metals and themes. Due to the popularity of all types and time periods, we are launching a new series of articles that will run through the beginning of 2017, titled Ringing in the New Year. Each week until the beginning of January, we will share a story about rings — from the history of certain styles to exhibits and modern designer pieces. We’ll interview the most stylish women we know, including collectors, retailers, antique dealers and designers, for heartfelt stories, humorous anecdotes and how-to articles.

What better way to kick of the series than with the exhibit Rings Around the World curated by Sandra Hindman, founder of Les Enluminures Gallery (with locations in Paris, Chicago and Manhattan). The Rings exhibit, which runs through Dec. 3, 2016 at the New York gallery, focuses on what Hindman refers to as “the universality” of rings and how certain ideas in this category of jewelry have occurred across cultures and throughout time. (See the review of the accompanying catalogue to the exhibition here). The rings will go on sale after the exhibit.

Hindman, a professor emerita of art history at Northwestern University, launched the Paris gallery in 1991 with a focus on medieval and Renaissance illuminated manuscripts, which led her to curate and co-curate exhibitions of rings of the same time period and beyond. She also is the author and co-author of the books associated with the showings.

“Although the exhibit is titled Rings Around The World—it is not a history of these rings but rather a perspective on how rings represent certain eternal forms and functions from the Bronze Age through the present and across different cultures and continents,” Hindman explains.

She began to collect the material for this show when she was working on her first exhibit and book about medieval rings over 10 years ago. “As I began to purchase rings—I realized that I was becoming more and more interested in what they represented and continued to represent rather than putting them into a formal art history context with, say, monuments or decorative arts.”

“Gradually I divided the collection up into four themes: Rings Speak, Rings Protect, Rings as Sculpture, The Future of the Ring.” Says Hindman.

As Hindman and I walk through the different rings in the exhibition, I am most drawn to the Rings Speak section.

“The percentage of historical rings that speak is very high compared to other rings,” Hindman reports. And there is definitely fluidity among the themes. Rings that speak could also be rings that protect and so on,”she adds.

It is the most intimate and intriguing part of the collection. All of the rings in this section, from posy to rebus to memorial rings resonate on a deep emotional level. Hindman’s theory is “rings encircle the fingers—the part of the body which has the most nerve endings. The ring functions almost like an extension of the person.”

“The voice with which a ring speaks is one of the most interesting characteristics of rings with words,” Hindman continues. “It can speak as the wearer, the giver or the actual ring.”

Personally, for me, it’s all in the sentimentality and the symbolism, the meanings and the messages that can make me smile or tug at my heartstrings whether it’s spoken in words or images or both.

The first ring that Hindman found for the collection was a Chinese archer’s thumb ring in light nephrite polished jade with bas-relief of Chinese characters from the late 17th or early 18th century. “It simply says quit/ abstain from alchohol/wine. Archer’s rings developed over time from practical tools of war to pieces of jewelry that are also symbols of the status and wealth of fashionable gentlemen. “I thought it would be perfect for this exhibit. Like the posy rings of the same time period –it addressed the wearer in some way although neither were influenced or inspired by each other.”

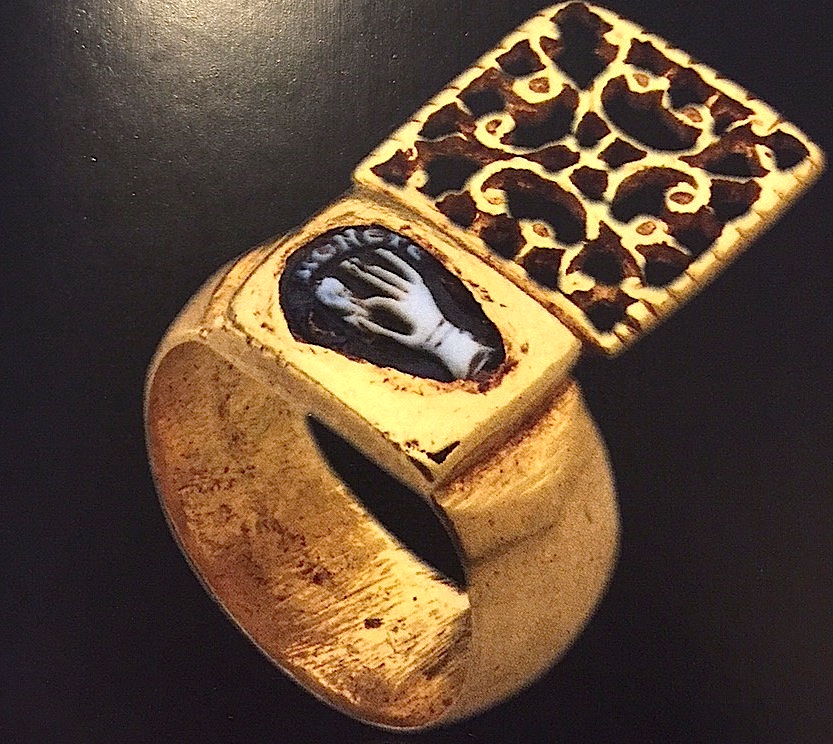

A late Roman key ring was crafted with an elaborate openwork design of a gold Roman key motif with a cameo that depicts a hand pulling an ear and carved with the Greek word meaning “Remember.” Hindman says, “this is an example of pictures and words speaking together to form the message of the ring. It is symbolic of marriage in Roman times—the word ‘Remembered’ is for the wearer (the wife) to think well of the giver (the husband) . The key pattern is indicative of the custom of the wife taking on the household management.”

Within the exhibit there is also the Renaissance belt ring with the inscription Svis A Vovs, from 16th century England or France. This is also a ring that reveals its message through words and symbols. In various earlier cultures the belt represented fidelity, fertility, childbirth and “hold tightly to me.” The giver of the ring is declaring his love in both the motif and the inscription, which translates to “I am yours.”

Posy rings (with the name coming from poetry in French) date back to the Middle Ages. They could have elaborately enameled symbols of love on the outside or simple gold bands, but both would have inscribed verse or mottos on the inside. They continued throughout history and were even mentioned in Shakespeare’s plays. In the 17th and 18th centuries. Publishing of pamphlets of amatory verse became quite popular and allowed jeweler’s clients to choose their own personal expressions—for gifts of friendship, familial and romantic love or declarations of religious devotion. By the 18th century, posy rings were given as betrothal or wedding bands. The posy in the exhibit reads “God gives increase to love and peace” and is from England, circa 1660.

Two outstanding Gimmel Fede rings are showcased within the section Rings Speak. The clasped hands date back to Roman times and gets part of it’s name from the Latin mani in fede (hands in faith) and gimmel, which refer to the double hoop comes from the latin gemmelus for twins. The hoop swivels in the back so that the hands can open to reveal reveal a heart, twinned hearts or an inscription.

The earlier Gimmel Fede ring featured is designed with enameled hands with a heart on the outside of the right hand, with the inscription “Ghetrovt Tot- In Den Doot” on the inside of the bands. It is from the Netherlands, circa 1600-1650. Fede Gimmel rings were became a fashionable and popular form betrothal or wedding rings and this particular one translates the sentiment “faithful until death.”

The later Gimmel Fede ring with the inscription ‘Gage D’amitie’ is circa 1750 and displays multiple symbols of love—crowned hearts, fede hands holding the double hearts, and the entwined gimmel bands that alluded to the continuity and eternal bond of marriage. The gemstones also are part of the romance of the ring—one heart is in ruby for passion and the other in diamond for endurance. The inscription is on the inside—a token of friendship is intended for the wearer to see.

There are also a grouping of rings inscribed with Gold gab ich für Eisen on the outside, which translates into “I gave gold for iron.” These were considered patriotic rings and were given to all who gave up their gold to support Germany’s war effort during World War I. “In the case of this ring it is the wearer who is the ‘I’ speaking in the inscription and meaning of this ring. The grouping of five in the exhibit are from Germany, 1914.

“The rebus rings were truly fantastic as they spoke in images” says Hindman. The one in the exhibit is a memorial rebus and is French, circa 1770-1790. There is a scene painted on ivory, which depicts a young maiden standing next to an altar of love with turtle doves, In one hand she holds a lover’s crown of myrtle, and in the other, strokes a faithful dog. Above the scene is a rebus in gold lettering made of fine gold wires set against a background of tightly woven brown hair.

“In the Middle Ages rebus rings became popular in heraldic jewelry especially signets. This rebus with a J and E spells ‘Je”, a glass which is ‘verre’ in French and the letter L standing in for Elle. Together these spell out the message Je verre elle, meaning ‘I adore her.’” Hindman explains. The ring is also characteristic of the Neo-classical period when imagery such as urns and broken columns were couples with mourning figures, weeping willows and altars of love.

A later mourning ring from England and dated 1836, depicts a butterfly cameo. The symbolism of the butterfly in Western culture dates back to the classical myth of Cupid and Psyche in second century AD. Pysche means both butterfly and soul in the Greek language. “The romanticism and naturalism of the late 18th and early 19th centuries featured butterflies prominently in sentimental jewelry given as tokens of love or mourning.” explains Hindman. This was inscribed with the deceased’s name and date of birth and death.

Rings Speak includes quite a few more rings of beauty and language. This theme as well as the three othes will appeal to those of you with an affinity for rings, history, art and the different contexts in which these small forms of vast expression can be seen.

Try to catch the exhibit if you are in New York City before December 3rd, 2016